As I stepped onto the beach at Olifantsbos in the Cape of Good Nature Reserve I realised that something was very… different.

The tidal range in the Cape is usually modest, rarely dropping more than a metre and a bit. But today the ocean had retreated well over two metres and the treasures of the intertidal zone were exposed to the bright morning sunshine.

The retreating tide let great heaps of kelp on the beach, picked over by birds & devoured by sand-dwelling beach-hoppers.

Vast kelp forests lay limply in rubbery sheets; boulders that were normally hidden underwater were thick with limpets, mussels and predatory whelks, drilling through the shells of fellow gastropods to feed on their liquidized remains.

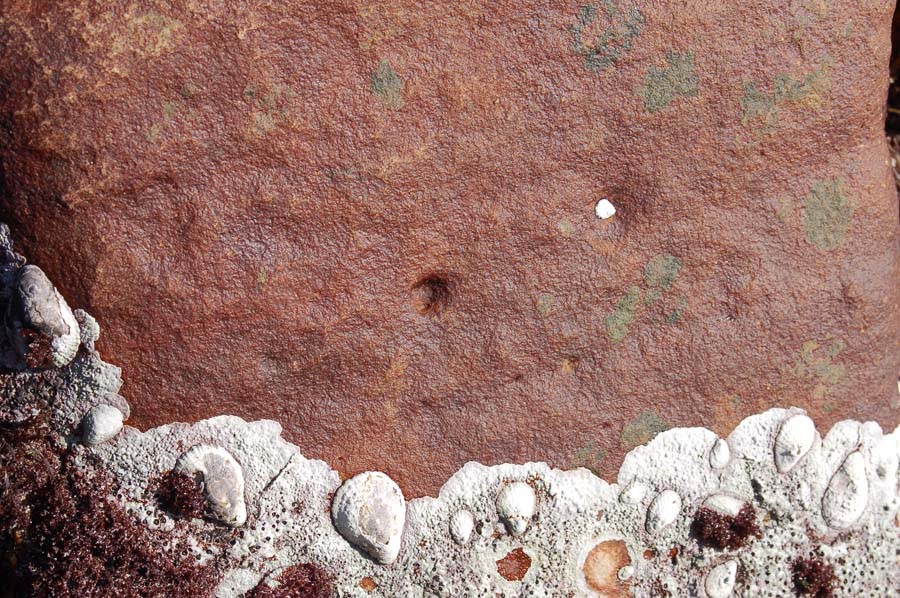

Exposed rocks turned out to be encrusted with shells and seaweeds, resembling dinosaur skin.

Our Strandloper ancestors feasted on these limpets & mussels; shellfish middens – rubbish dumps – are found all along the Cape coast.

Rock pools were home to cushion stars – a stubby limbed starfish – and neon-coloured but poison-tipped anemones.

Sandy Anemones catch prey with their stinging tentacles but their poison is harmless to humans.

Anemones can reproduce sexually or through simple division of the body.

Cushion stars feed by extruding their stomach directly onto algae & also lay eggs that hatch directly into tiny starfish.

But I wasn’t alone. Although I was the first human on the beach, plenty of other animals had beaten me to it. Hoof prints betrayed antelope and mountain zebra, soon seen grazing in the grassy dunes. Geese and ibises were foraging along the naked shoreline, competing for food with stern-faced kelp gulls – the skinheads of the bird world. And it wasn’t long before I saw the baboons.

Baboons leave their distinctive prints in the morning’s wet sad.

The alpha male was the last to leave the rocks but only after feeding for an hour.

It’s a pity the Cape Peninsula baboons are so maligned. Conflict with humans is inevitable in such an environment but these are the world’s most-southerly primates apart from our own species, and they have a very interesting trick up their sleeves. Other than us humans, they are the only primate to actively forage in the intertidal zone.

And there they were, sitting on rocks next to thumping waves and feeding on limpets and crabs, just like the indigenous humans here – the Strandlopers (Beach walkers) – used to do hundreds of thousands of years ago.

Oh yes, hundreds of thousands of years ago. Humans have been working the Cape’s beaches since the Early Stone Age. Recent archaeological discoveries have astonished scientists: implements in a cave near Mossel Bay (a 4-hour drive from Cape Town) date back 100 000 years and include the world’s first known container (an abalone shell) complete with painting kit – colours and applicators.

And it’s easy to see how the Strandlopers survived. The low tide bounty of shellfish is impressive but it’s nothing compared to the food that simply washes up on the beach. In the last few months I have come across stranded – but alive and edible – elephant and Cape fur seals as well as a sunfish the size of a child’s paddling pool. Six months ago two humpback whales ended up on separate beaches in the Cape Town area. That’s a lot of free meat.

The Cape reef-worm makes colonies of cement tubes, periodically taking over parts of the intertidal zone.

The usual tide line…

At some indecipherable signal, the baboons moved off the rocks and back onto the beach, leaving their hand and foot prints etched in the sand. The big male was the last to leave. He’d fed with his back disdainfully turned towards me but I had seen him flash a few peeks at me over his shoulder.

He came quite close now, still pretending to ignore me. Mr Cool. Then he looked at me – blank, primal. It’s usually at this moment when one realises how big these Cape Point baboons are; and remembers that their incisor teeth are longer than those of a lion.

Up in the dunes some juvenile baboons began fighting, filling the air with horror-movie shrieks of pain and panic. A skinny one, still wet from a previous beating and dousing in a rock pool, was being punished again; mothers scooped their babies up to their bellies and making an anxious, low-grunting noise. The male baboon turned and made his way to his family. I walked some more and did the same.

Hi Dominic,

Thanks for sharing these fotos, and your insights. We thoroughly enjoyed our Shipwreck Beach hike with you last fall. Was this extra low tide a projected seasonal event, or something else?

The intertidal zones are such a vital part of the marine ecosystem. Unfortunately, ours are suffering from various human impacts.

Best,

Mary and Vernon Rail

I have to admit I got lucky and arrived unknowingly during the very nadir of an acute spring tide. I now consult a tide table! You’ll be glad to hear that the Shipwreck Trail is as rewarding as it was when you were here. Last week’s hike got us baboons, eland, bontebok, ostriches and a tortoise. The smaller of the shipwrecks has, however, been almost covered in summer-blown sand; I’m wondering if winter’s approaching storms will reveal her again.

At last some raloniatity in our little debate.

Hi. I vaguely remember, when last visiting Cape Point many years ago, my sister showed me a midden built by the strandlopers. I went down to Buffels Bay and Black Rocks only to find a rather modern looking chalk oven circa 1890. This is NOT what I remember seeing. Any idea where it is or (sadly) whether it has been destroyed? I do not recall chalk but shells.

Many thanks. Look forward to hearing from you.

Regards. Bebe

The kalk oven was restored in the 1990s – it was once used to burn limestone hacked out of the hills behind it (to make lime for cement); it is some of the only limestone on the peninsula. Fascinating to hear you saw a midden there: modern humans have been on the Cape peninsula since the early stone age and I often come across great drifts of limpets and mussels – old middens? Anyway, the vegetation on those hills and flatlands around the oven is now very thick – I guess the middens you saw have been buried under bushes. The fynbos that side (False Bay) is due for a burn so maybe that is what will reveal them again. Thanks for the contribution.