I realised I started this blog all wrong. It began as a lament to the loss of nature – the rainforests are burning, the coral reefs are dying – but I should, in fact, be marvelling at the robustness of the natural world. Nature is everywhere if you know where to look, and when you live in Cape Town, there is a lot of nature to look for.

Sitting at the top of a peninsula that has more butterfly species than Britain, more types of plant than Canada and five per cent of the world’s marine coastal species, Cape Town is the kind of city that you need only stroll through a garden, go to the beach or drive around the local sewage works to see fantastic things – lizards and sunbirds, dolphins and seals, flamingos and pelicans – and that’s before you get to fire-ravaged wastelands.

The title image is a Cape Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra zebra), Africa’s rarest type of zebra with a population of under five thousand. (That’s the good news – they were down to 60 individuals a hundred and twenty years ago.) Did I have to trek into a remote mountain wilderness to glimpse this beauty? Pah! It was hanging out next to the road in the Cape of Good Hope Reserve, an hour’s drive from the centre of Cape Town. Here’s what else has caught my eye over the last few weeks on my nature tours.

We’ll start off easy. My garden is full of Cape Skinks (Trachylepis capensis), scuttling around on sunny days chasing after insects. Like most skink species, the Cape skink gives birth to live young but can somewhat curiously also lay eggs. And despite its rather short legs, this one is built for running; other types of skink have evolved to ‘swim’ through dense vegetation or soft sand and have consequently lost their limbs giving them a snake-like appearance.

I pulled over during a drive down to the Cape of Good Hope Reserve. It’s whale season at the moment in Cape Town and Southern Right Whales (Eubalaena australis) have arrived in large numbers from the Antarctic. A small cloud of mist had signalled a whale, and there it was in the ocean below the road. This one was accompanied by a couple of dozen dolphins, but when its great back curved out of the water, a small dorsal fin could be seen – that meant a Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). Smaller than Southern Rights, Humpback Whales migrate past the Cape in the summer months so to see them in October was unusual. Turns out that a wave of krill had washed into False Bay and Humpbacks had followed it in. It’s hard to get good images of whales but their presence is magical. A simple puff of air from their blowholes prompts gasps of delight from onlookers; the appearance of a flipper triggers a machine gun-rattle of camera shutters. Huge, slow, once hunted without mercy, I am genuinely astonished that these titans of the ocean are still around.

A trip to the West Coast National Park in the Cape spring (August – October) is worth the hour and a half’s drive from Cape Town. Having gorged itself on the winter rains, the vegetation explodes into colour, rewarding visitors with fields of flowers that rival those of the more famous Namaqualand region several more hours to the north. This is one of the Spider Lilies (Ferraria crispa), a member of the Iris family and called an Inkpotjie – Little Inkpot – in Afrikaans. Its scent is somewhat of an acquired taste – think rancid vanilla – but is irresistible to flies, which seem to be the flower’s pollinator. The odd appearance of the flower could well be part of this: the furled edges resemble a ragged, open flesh wound and the purple colour looks to me like dried blood.

Strandfontein Sewage Works has long been on my list of Cape Town’s best nature spots and here’s one of the reasons why: you can see Spotted Eagle-owl (Bubo africanus) there along with harriers, kites, buzzards and fish-eagles. I’m afraid I woke this one up with my frantic scrambling to find the camera and received a baleful look in return. Standing just under half a metre and weighing a shade under a kilogramme, it’s a big bird that preys mostly on invertebrates but will take small mammals and birds up to the size of a nearly-full grown guinea fowl. The elaborate ear tufts are thought to play a role in display but also function to break up the bird’s outline, making it harder to see against its background.

An orchid, Satyrium erectum, makes a brief appearance next to the side of the road in the Overberg region, an hour’s drive from Cape Town. This one likes the heavier clay soil environment of renosterveld, the type of vegetation that used to carpet what is now wheat fields and orchards. Once home to rhinos (renoster) and lions as well as herds of antelope and zebra, nearly all the renosterveld has been ploughed up or urbanised but fragments remain on farms and in reserves – read an Introduction to Renosterveld here.

The baboons of Cape Point (Papo ursinus) usually attract a lot of negative press. They steal bags, clamber onto – and sometimes into – cars, and really know how to ruin a family picnic. But apart from humans, there are no other primates further south in the world than these, and they share our habit of foraging for food in rock pools at low tide. Shaggier than their savannah counterparts but still the same species, these Cape baboons are in constant conflict with humans and you’ll often see them running off clutching a cheese sandwich with a red-faced human chasing after them. But make it clear that you don’t have food and they ignore you.

The blackened twigs are a reminder of the devastating fire that swept through the mountains of Betty’s Bay close to Cape Town at the beginning of the year. Nine months later, this coastal region has erupted into bloom. These are orchids again, Satyrium carneum, and, thanks to the rejuvenating nature of fire in fynbos, they were flowering in their hundreds when I visited in early October. By burning off the choking layers of old plant material, the fire returns nutrients to the soil through the ash and at the same time wipes the slate clean for every buried seed and bulb to germinate under full sunshine. Find out more about Fire and Fynbos here. https://thefynbosguy.com/category/fire-fynbos/

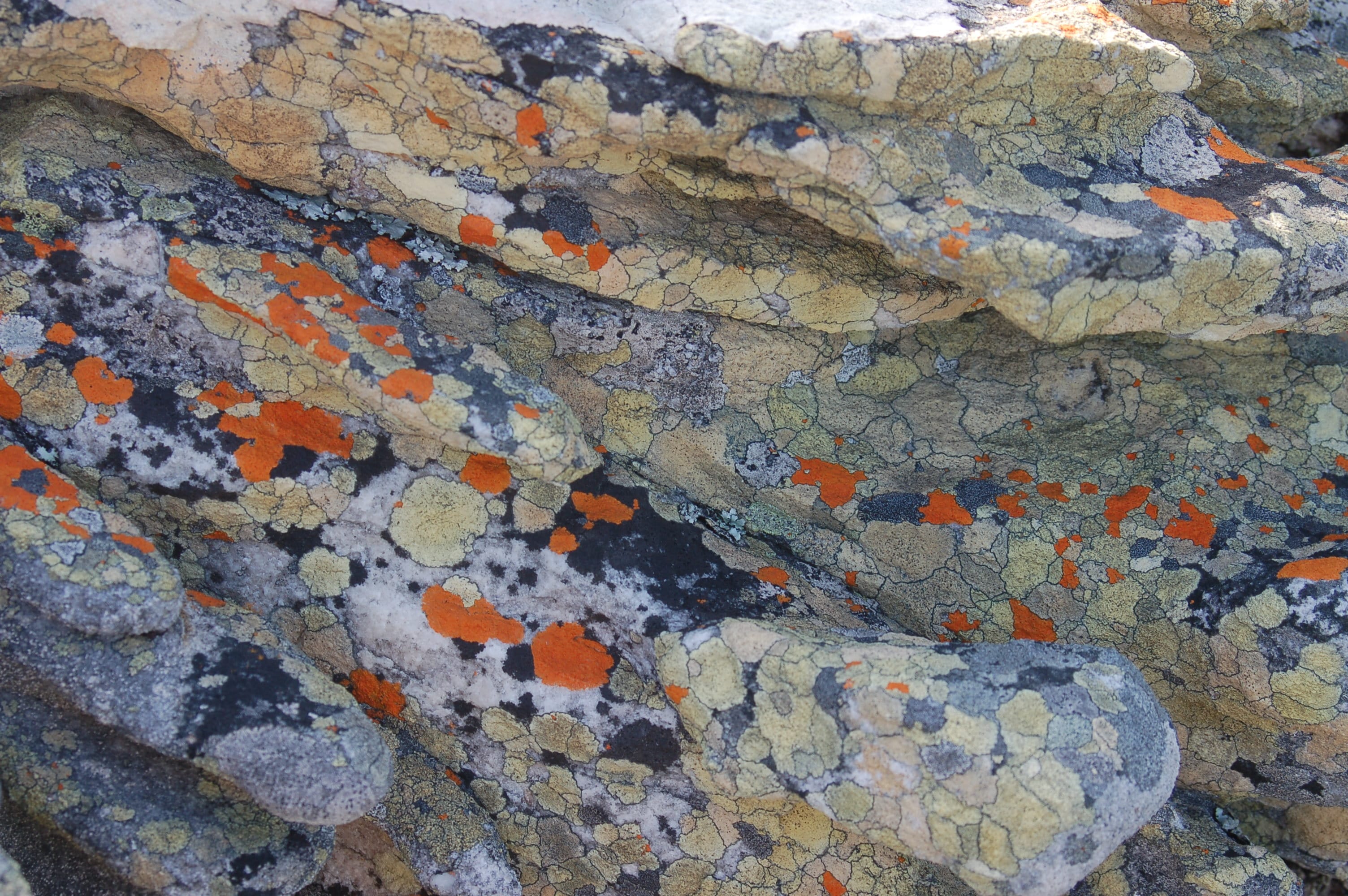

Every time I see a lichen I have to remind myself that it is a symbiosis between algae and fungus, living in harmony and creating a new thing – a lichen. How does it work? The fungus takes care of the shelter, water and nutrients; the algae photosynthesise and so provides energy in the form of sugar. A third party – a yeast – may also be involved in many lichens. These ones were near Cape Point, coating rocks close to the Atlantic Ocean.

A little further along the beach and I came across a dead Eland (Taurotragus oryx). Part of a large herd in the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve, it is Africa’s largest antelope and weighs up to 800 kilogrammes. No wonder Eland make up 90% of animals depicted in Khoisan rock art – there’s a lot of steak on an Eland. This one would have died of natural causes – it’s been a while since big cats and Bushman hunters prowled the Cape Peninsula – but had I been walking here 400 years ago, the chances are that I would have surprised black-maned Cape lions or brown hyenas scavenging on the corpse. Or rather, I would have been surprised.

The burnt sand of Betty’s Bay also yielded a real rarity: Disa sabulosa, an orchid with a tiny range of around six square kilometres (Bettys’ Bay basically) and the infuriating habit of flowering only after fire. Only a few centimetres tall, its population is thought to be down to under a thousand mature plants; but it hangs in there, rewarding us with its sculptured elegance every few years. And like with all nature, all the more reason to enjoy it now.

Most interesting. If you distribute a newsletter I would like to receive it.

Thank you Chris – I’m afraid I don’t do a newsletter although I do try and write a blog each month. But you have given me an idea…

Hi my name is Anwar. Me and my girlfriend was at the West coast national park on new year’s day.. and we experience the best day ever. We saw a total of 5 different snacks crossing the road. I raced an Ostrich. And stopped for 10 tortis. Not to mention the spectacular legoon and clear water. Iv got some pictures and videos that I want post but I dont know were I can send it .. please forward me a email address or website that I can send it . Kind regards.

Hi Anwar – looks like you saw some good stuff at the park – 10 tortoises is quite a sighting (SA has the world’s highest diversity of tortoises). As for where to post them, I’m not sure other than the usual instagram and facebook; have a look on facebook and see if there is a ‘West Coast’ group or something like that: there is, for example, a Fynbos People group on facebook where people post these kinds of things. The handsome antelope by the way, the bontebok, was once reduced to 17 individuals before the settlers stopped shooting them – it’s a very lucky animal!